In a previous blog, we concluded that Conway’s law will prevail and that microservices are essential in a world of Enterprise DevOps. This means that anyone who is serious about DevOps should learn how to define microservices, how to manage them, how to maximize the benefits and how to minimize the issues. It is important to know how to design ideal microservices for different technologies and different use-cases. This blog gives an overview of how microservices will support the business in an optimal way.

What is a microservices architecture?

James Lewis and Martin Fowler give us the best definition of microservices architectures:

The Microservice architecture style provides an approach to building larger applications as a suite of smaller services (=IT components or Apps), where each service:

- Is built around a business capability

- Runs its own process

- Communicates via a lightweight mechanism, and

- Is independently deployable by automated deployment machinery

In the end, microservices should promote business flexibility. This is achieved if new feature requests have the maximum probability of impacting only one single microservice, enabling a DevOps team to fix the problem fast, quickly re-test with automation, and re-deploy the microservice.

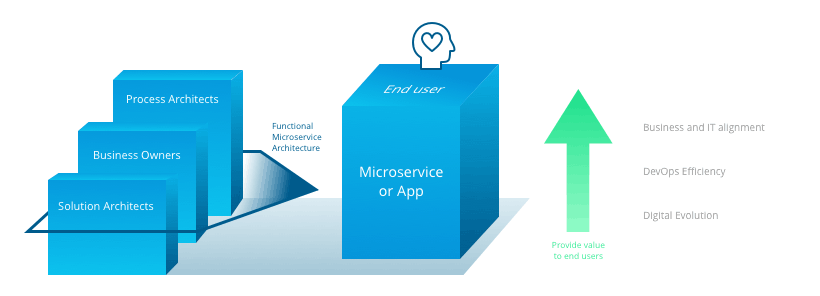

What are functional microservices?

Since most feature requests come from end-users, most microservices will be functionally oriented. Feature requests will usually involve changing GUI, logic, workflow, and data, so designing microservices that have all these parts in the same deployable will minimize the impact of change.

The design will involve much more than technical considerations. We have seen that the business process is usually the best basis for dividing a functional scope into good microservices. This, in turn, means you should involve business owners and process architects to define the architecture.

Do we still need technical microservices?

A few microservices will be more technically oriented and callable via clear and stable request-reply interfaces. When a piece of functionality should be the same for many purposes, and when it does not change very often, it can be broken out into a separate more ‘technical’ microservice.

Other microservices can be integration oriented for orchestrating other services, or responsible for connectivity to some other large system and/or external party. A central ESB is often replaced by distributed specialized microservices that can hold their own business data if it makes the service more efficient.

Companies should be open-minded about what a microservice can and should do. The best microservice architecture for one business area is not always ideal for another area. This aligns with DevOps where we mostly delegate design decisions at the team-level.

It’s important not to re-use too much or think that this is SOA version 2.0. We will elaborate more on this important topic in a separate blog coming soon.

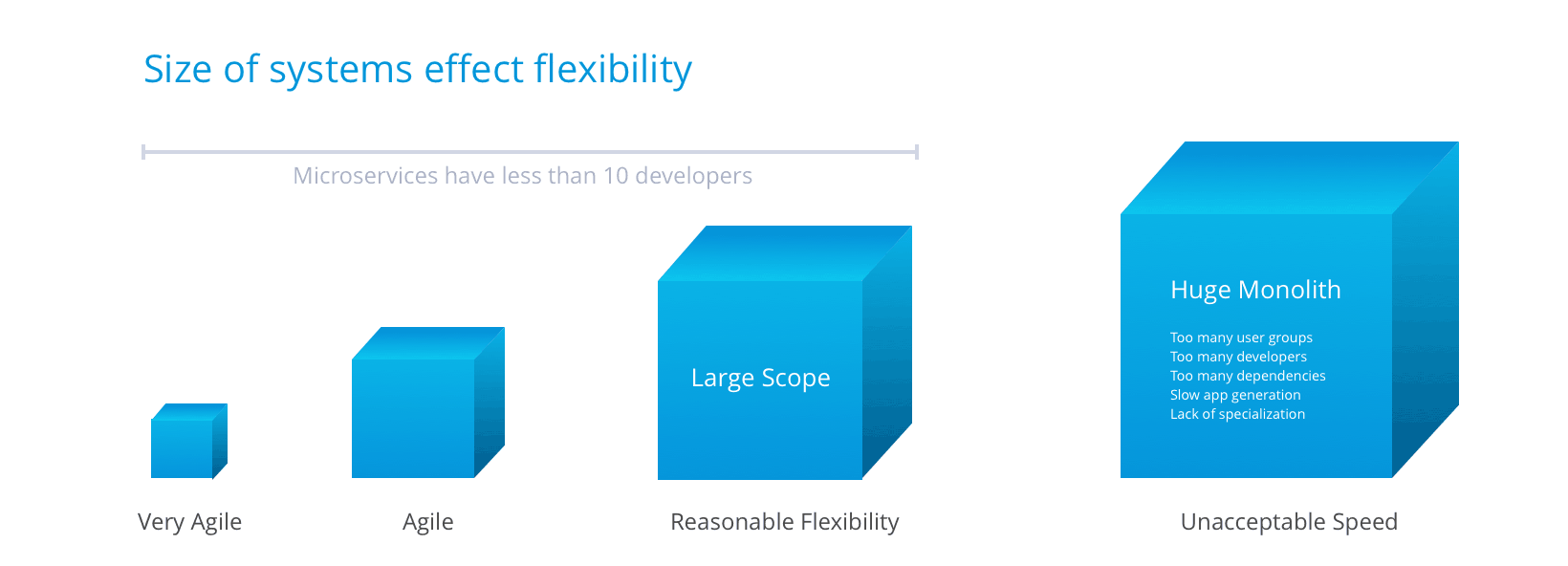

How does a component’s size affect business agility?

For microservices, most people say that a DevOps team of one to 10 people should own, build, operate and manage approximately one to five microservices. Size is relatively flexible for designing microservices.

For small to relatively large scope, it is not necessary to split things into smaller pieces than the business is asking for. For example, the teams and the architecture can be aligned with the business functions they support, achieving maximum autonomy to evolve easily and generate value.

However, when the scope of the “System” is very large, it will always be better to split the functionality into separate microservices. The internal and external dependencies grow when years of time-critical fixes and short-cuts create unwanted dependencies. It’s hard to change the system, significant regression testing for every release and deployments are costly and risky.

Figure 2: In a Monolith architecture the user groups fight for attention and the developers step on each other’s toes.

The ideal size of a microservice is related to the number of developers. This means that HPA platforms have an advantage over open source because they can split later, have larger microservices, or have smaller teams.

What is not a microservice?

Having promoted a flexible view on microservices it makes sense to compare with what is not a microservice:

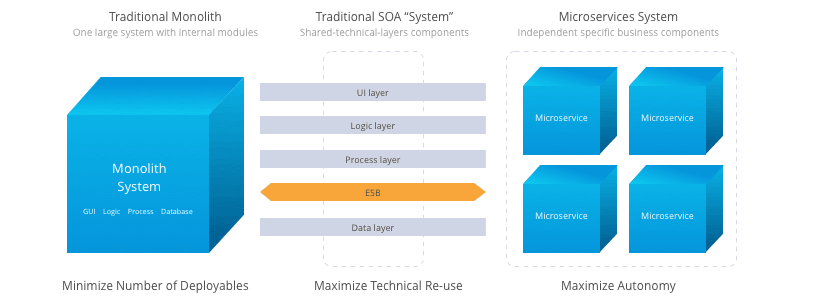

- Monoliths are not microservices because they are too large. They require development teams of more than 10 people and (usually) have many functionally separate processes in the same deployable. This requires more regression testing and longer release cycles. Dependencies grow with size and over time, and they are not explicit via service calls as they are with microservices architectures.

- Layered SOA Architectures where the Business Data is below the ESB are also not microservices. They do not contain required data and functionality for a business function in the same deployable. Instead, almost every business feature stretches across several technically focused “layers” of shared deployable units. According to NGINX: “SOA is built on the concept of a share-as-much-as-possible architecture style, while microservices are built on the concept of a share-as-little-as-possible architecture style.” Microservices should be autonomous and fulfill a business function so they have GUI, logic, workflow and a database to store things when they need to.

Figure 4: Microservices promote better flexibility and business-IT cooperation than the other patterns.

Our view: Common characteristics for microservices

Microservices fulfill a business function and communicate with each other as part of the regular business process, making them easier to understand for non-technical people; This is a good thing for DevOps and team-decisions. In our view, good microservices should have the following common characteristics:

1. Process oriented

Functional microservices usually implement a phase of the business process or a full business function. The name “service” is misleading. The microservice can be a callable service, but it can also be an app that focuses on end-user functionality.

2. Autonomous and flexible

Microservices should be developed separately, deployed separately and contain their own data. They should be evolving in time and easy to change and re-deploy.

3. Automation and control

Microservices should have good test and deployment automation, error handling, monitoring and alerting, and should allow feedback from users.

4. Right-sized

“Micro” is also somewhat misleading, microservices should not be too small or too large. The service can be relatively large with up to 10 developers. It is smaller than a monolith, but it does not have to be smaller than a normal app. If using a high-productivity platform like Mendix, a microservice can almost be a core system of a medium sized company.

What will microservices mean for you?

Microservices, if done correctly, promote business and IT alignment and improve flexibility in the operational processes. With previous paradigms, it has been very difficult to change business processes, so digitization has been very difficult for most incumbents. DevOps and microservices architecture solves this problem by localizing the decisions and the development: The DevOps team is working directly with the business and is autonomous to take decisions. The microservices are developed separately, with minimal dependencies, and they are deployed separately as autonomous units.

Mendix provides on-site workshops and training on microservices. We have helped a large number of customers with new programs and initiatives, providing support in decision making and working through the most optimal solution for each business problem. Contact us for more information.